Journal of Science | 2008 | INFO

Journal of Science | 2008 | INFOThe Archaeology of Nothingness

Georg DiezMartin Fengel has a benevolent gaze. He sinks down gently onto things, he strokes the edge of the table and rests briefly on the coloured board, he touches the strange egg carefully, then comes his gaze, and he puts it down again straight away. This gaze is benevolent because he leaves things as they are; this gaze is lovely because he is happy and astonished that these things even exist.

Martin Fengel is fascinated by the wealth of the world. In that respect he comes close to science.

There’s that one maxim by Ludwig Wittgenstein, who wanted to bring all science back to the basics of philosophy; there are even quite a few maxims by Wittgenstein which are very appropriate to what Martin Fengel is doing. It is almost as if Fengel wanted to demonstrate what Wittgenstein meant. In Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, for example, Wittgenstein writes, “What can be shown cannot be said”, referring primarily to language in its elementary form. He also says, “A sentence shows a logical form of reality. It emphasizes it.”

Wittgenstein was referring to language (he was thinking about the grammar of the world in an age when images had not yet begun to play the key role in determining this grammar), and yet Martin Fengel’s pictures work with the same model and the same rigour that Wittgenstein advocated. They show the logical form of reality and emphasize it; they are formulae, they are the keys to our understanding of what we see; they contain what could be termed the

optical DNA of our world.

This clearly distinguishes them from almost all other photos and images in our age replete with images. Fengel’s photos neither explain nor comment on what they show; they do not adopt a stance, show affection or criticism; they do not adhere to reality but float above it; nothing sticks to them, they are free from the past, they elude narration and refuse to pay homage to the story; yet they are setting a sign, just as they themselves are looking for signs. These pictures store optical codes which in turn can be combined to form something resembling reality.

These pictures are about lines, about colours, about structures, but what Fengel photographs is not what the objects once were but rather what we see in them – neither psychological nor psychoanalytical but instead entirely phenomenological. Observation as an activity. Martin Fengel basically does not create photos; it is more that he uncovers pictures.

He is concerned with the basis of our understanding, nothing less than our approach to the world, and in this Fengel is one with Wittgenstein.

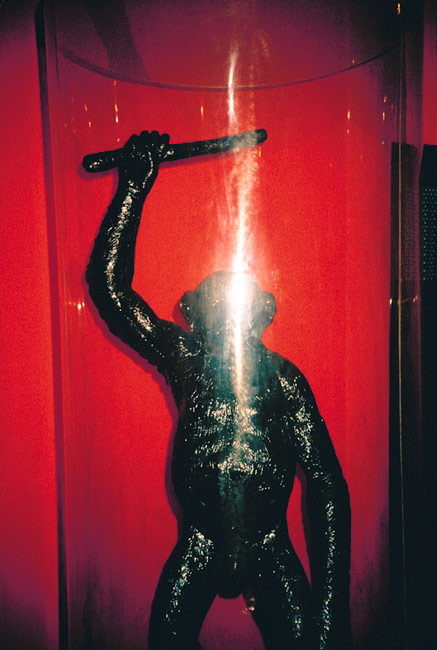

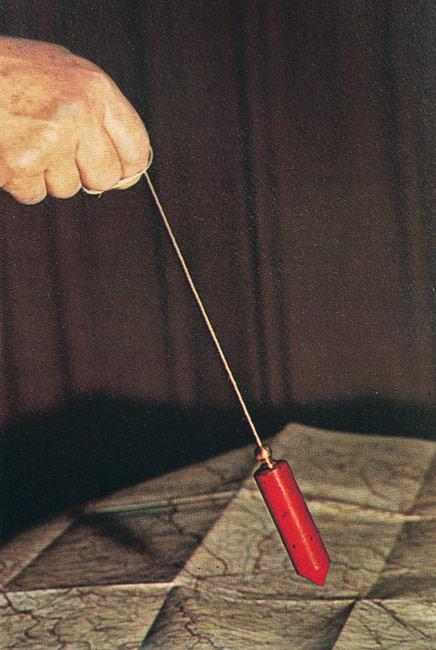

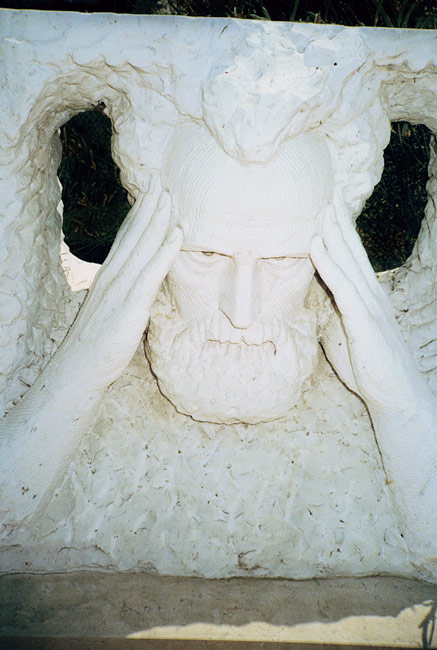

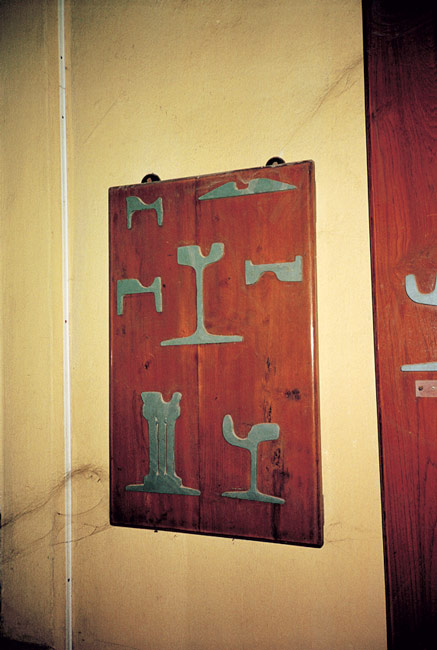

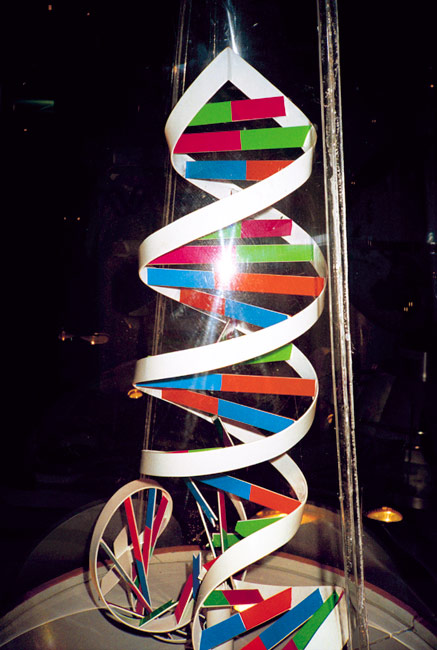

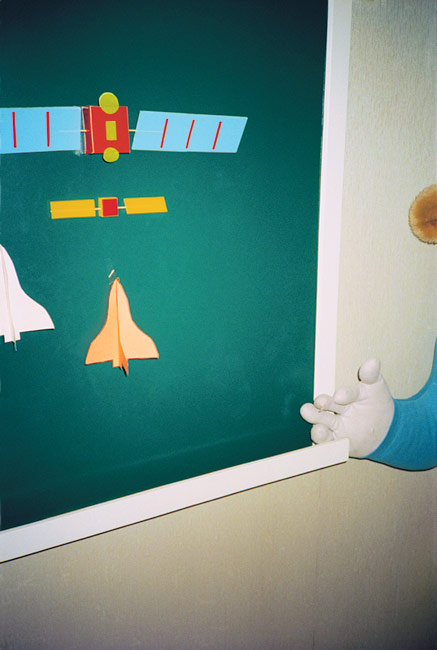

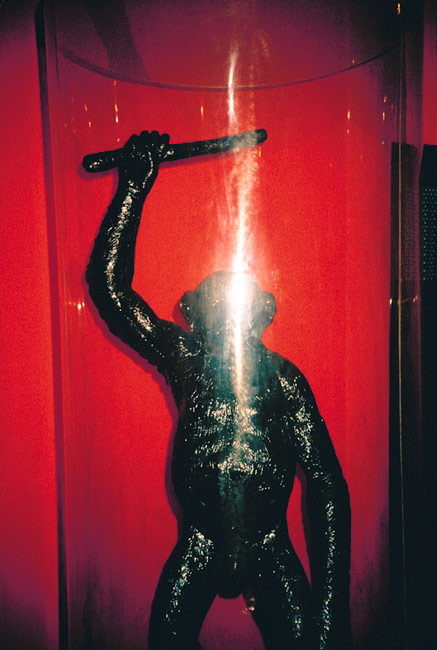

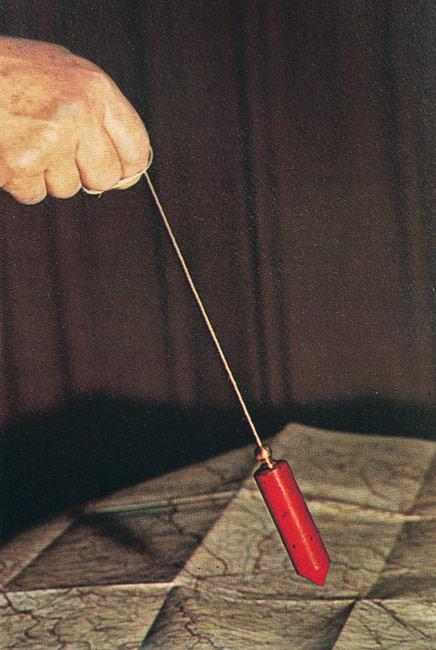

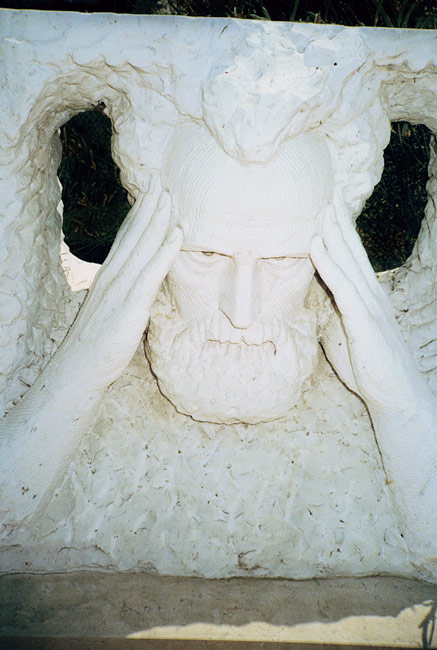

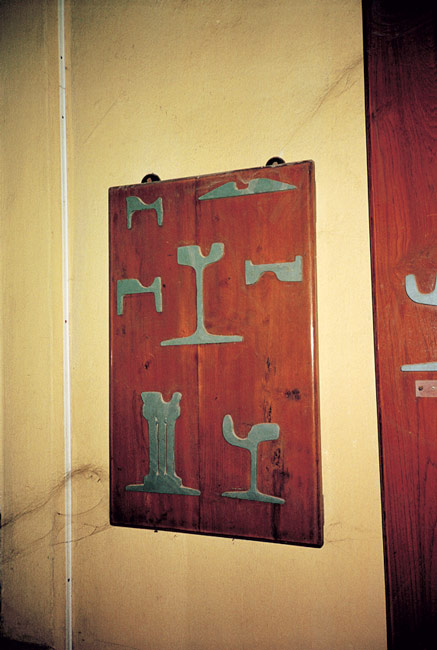

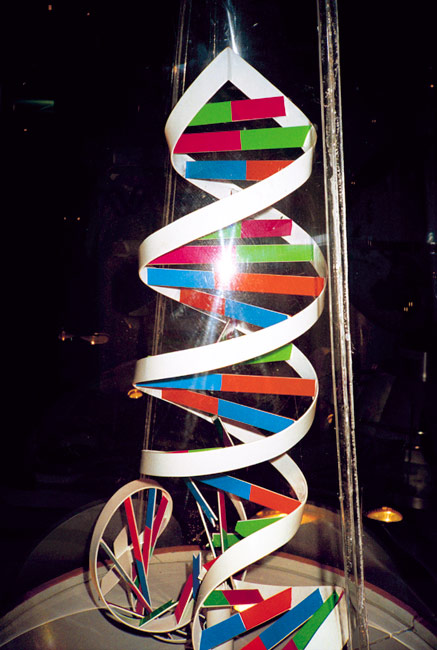

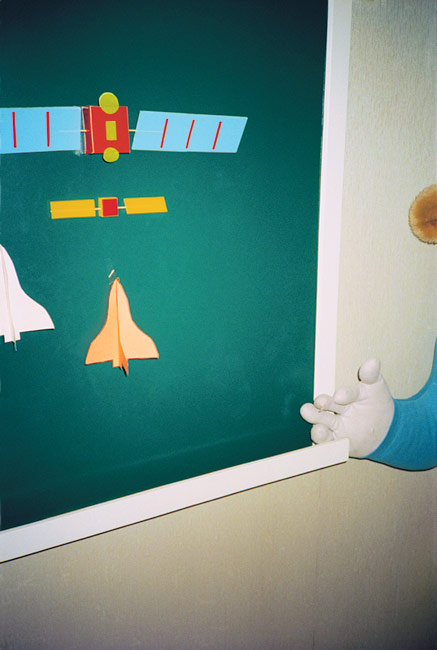

Wittgenstein’s axiom that the world is the “totality of facts, not things” can be taken a step further, and transferred to Martin Fengel’s “object photography” – because at first glance it does appear to be object photography. Yet the things he presents are precisely not objects but something approximating what Wittgenstein meant by facts – the relationship between objects, the “existence of atomic facts”, as Wittgenstein called it. This is more simply formulated by Fengel – as a piece of twisted wood in front of a white wall, and a mumbling Old Testament-style aged man made of marble; a red hook on a wall-hanging cupboard and a beautiful but impermeable chain of fish-like objects; a spiral which seems to turn DNA into the creative result of a children’s birthday party; a hand in a glove holding onto a school chalkboard.

“A picture is a fact”, said Wittgenstein. And Martin Fengel’s work is characterized by precisely this distanced, analytical approach. A picture is essentially not a picture for him, but the relationship between what is in the picture and what is in our heads. This is not connected to something resembling a prototype, indeed the opposite is true. It is about ignoring,

repudiating and forgetting what could be called prototypes. Fengel is fascinated by what is radically novel and thus wonderful. However this is not novel in the sense of something new, but in the sense of something different, something eternal, analysing what we see.

Being novel thus presents an epistemological paradox, because something can only be novel if it has a relationship to what is already well-known. Otherwise we would not perceive it as novel, indeed we would probably not perceive it at all. These inquisitive pictures are therefore about the structures of reality, the fiction of reality, models for approaching this reality, and agreeing about the nature of reality and the world that we live in. That is more or less what Wittgenstein called a fact.

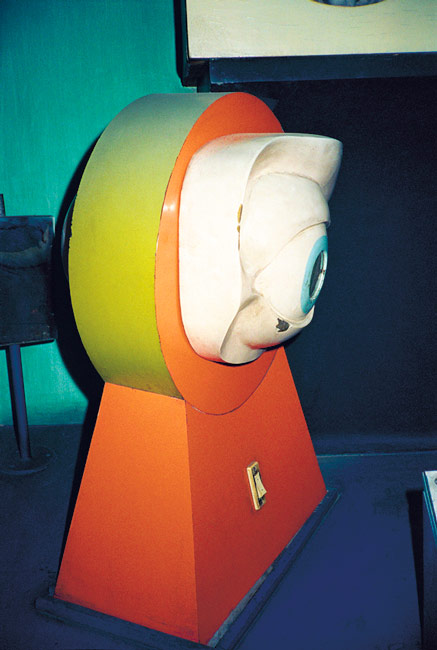

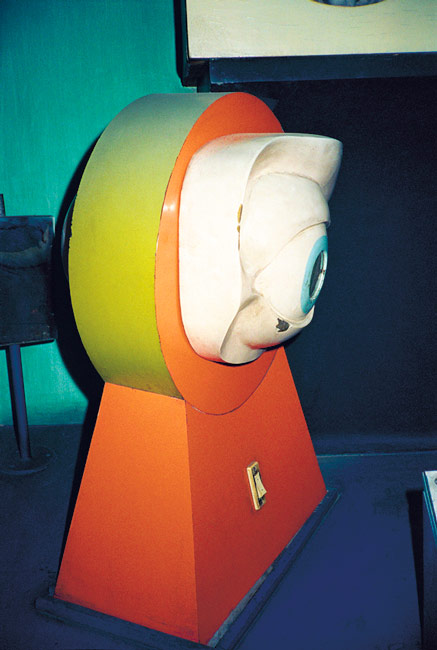

Yet Fengel does not take the mystery away from the objects. The more precisely he looks at them – the wood, the ape, the giant eye – all the stranger and more unsettling they seem. The closer he comes to the objects the more they retreat – it is a science of observation which depends on the contradictory experience that precision produces blurring, that refinement creates coarsening, and that orange is sometimes merely orange just as blue is nothing more than blue.

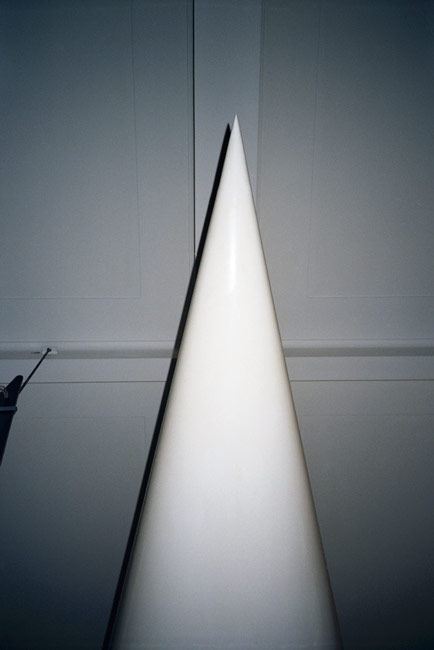

It could be said that his photos are works spread over the pictorial dissection table. The lens is his surgical instrument and our world is the object. Martin Fengel is conducting a kind

of present-day archaeology, but without the belief that a past that can be interpreted ever

existed. His pictures are thus always facing nothingness. As Wittgenstein puts it, “Form is the possibility of structure.”

Sense is a word that Wittgenstein applies very carefully, indeed almost scrupulously. Sense is something that Fengel’s photos almost entirely lack. Sense is something that science does not seek to find. Sense is something for a poetry album, for evenings accompanied by red wine. It is a stranger to reality. And only this reality counts for the positivist Fengel. “What a picture represents is its sense”, comments Wittgenstein.

And what the picture represents can by all means also be sensual. Yet everything that could be beautiful or could be seen as poetic in these pictures is a result of external attribution. The pictures themselves avoid this simple definition. These pictures, despite their clarity, are evasive. They remain material.

That is also because of their objects, or what we see and what we think we see. A mirror and a curtain, a zig-zag pattern on the floor, the picture of a hammer in a golden frame – Martin Fengel is a field researcher in his work, collecting, recording, archiving, roaming the world from Bangkok to Mexico or from Arkansas to the Munich district of Pasing. Some of what he finds is remote and some of it is everyday; Martin Fengel’s world does not distinguish between the two, and indeed – and this was the truth revealed by Pop Art – neither does the world itself.

This lack of differentiation in observing, this benevolence, is exactly how Fengel’s relationship with Pop can best be described. That, and the fact that he took up photography in the late 1980s and early 1990s, when it still seemed that the whole world had transformed itself into its own surface. Fengel certainly learned the positivism of Pop, fascinated as he is by the shell of our being, by the shapes of our life, by the game pieces of sense, and by the beautiful folds of nothingness. Yet he has kept his distance from a simple affirmation of what he sees and what we see.

He also learned something that he could take with him into the post-Pop era, our age, when pictures have turned and are again competing with one another. Nothing is harmless and nothing is as it seems. A direct gaze is all the more important, and it is all the more understandable that this gaze engenders a stance that might be called melancholy if it were not that our own sadness is reflected in these photos – photos that are in themselves only photos, and yet become so much more when the observer confronts them.

Now the art – the truth that Wittgenstein was referring to – is to stage this relationship between the image (which is reticent about its history and meaning) and the observer (who is looking for nothing more than that: meaningful connotations, biographical references, something familiar). It is astounding that the photos withstand this approach without actually rejecting it. It is precisely their distance that allows them to dispense some comfort in a melancholic world that knows no desperation. It sometimes seems that melancholy even serves as protection against too much contact with the hard corners and sharp edges of the world.

Melancholy and comfort are thus the cornerstones of this architecture of nothingness that Martin Fengel pursues in his photography. Melancholy and comfort are the result of this photographic activity rather than an intrinsic part of the aesthetic agenda. Melancholy and comfort are the new dawns in these pictures; they are what art can achieve, akin to what Rainald Goetz demands of art in Jeff Koons, his drama about artists and the 1990s: “That every picture, even abstractly, has to deal naively in the sensory information of world facts. And that there are therefore no solutions - for anything, that in its own way every picture is a completely new opening of the eyes, first thing in the morning, not knowing anything, that only later becomes complex and awkward, broken, difficult, ruined, etc. etc.”

So, world facts, right. And quite naive. Or just benevolent.

Journal of Science | 2008 | INFO

Journal of Science | 2008 | INFOThe Archaeology of Nothingness

Georg DiezMartin Fengel has a benevolent gaze. He sinks down gently onto things, he strokes the edge of the table and rests briefly on the coloured board, he touches the strange egg carefully, then comes his gaze, and he puts it down again straight away. This gaze is benevolent because he leaves things as they are; this gaze is lovely because he is happy and astonished that these things even exist.

Martin Fengel is fascinated by the wealth of the world. In that respect he comes close to science.

There’s that one maxim by Ludwig Wittgenstein, who wanted to bring all science back to the basics of philosophy; there are even quite a few maxims by Wittgenstein which are very appropriate to what Martin Fengel is doing. It is almost as if Fengel wanted to demonstrate what Wittgenstein meant. In Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, for example, Wittgenstein writes, “What can be shown cannot be said”, referring primarily to language in its elementary form. He also says, “A sentence shows a logical form of reality. It emphasizes it.”

Wittgenstein was referring to language (he was thinking about the grammar of the world in an age when images had not yet begun to play the key role in determining this grammar), and yet Martin Fengel’s pictures work with the same model and the same rigour that Wittgenstein advocated. They show the logical form of reality and emphasize it; they are formulae, they are the keys to our understanding of what we see; they contain what could be termed the

optical DNA of our world.

This clearly distinguishes them from almost all other photos and images in our age replete with images. Fengel’s photos neither explain nor comment on what they show; they do not adopt a stance, show affection or criticism; they do not adhere to reality but float above it; nothing sticks to them, they are free from the past, they elude narration and refuse to pay homage to the story; yet they are setting a sign, just as they themselves are looking for signs. These pictures store optical codes which in turn can be combined to form something resembling reality.

These pictures are about lines, about colours, about structures, but what Fengel photographs is not what the objects once were but rather what we see in them – neither psychological nor psychoanalytical but instead entirely phenomenological. Observation as an activity. Martin Fengel basically does not create photos; it is more that he uncovers pictures.

He is concerned with the basis of our understanding, nothing less than our approach to the world, and in this Fengel is one with Wittgenstein.

Wittgenstein’s axiom that the world is the “totality of facts, not things” can be taken a step further, and transferred to Martin Fengel’s “object photography” – because at first glance it does appear to be object photography. Yet the things he presents are precisely not objects but something approximating what Wittgenstein meant by facts – the relationship between objects, the “existence of atomic facts”, as Wittgenstein called it. This is more simply formulated by Fengel – as a piece of twisted wood in front of a white wall, and a mumbling Old Testament-style aged man made of marble; a red hook on a wall-hanging cupboard and a beautiful but impermeable chain of fish-like objects; a spiral which seems to turn DNA into the creative result of a children’s birthday party; a hand in a glove holding onto a school chalkboard.

“A picture is a fact”, said Wittgenstein. And Martin Fengel’s work is characterized by precisely this distanced, analytical approach. A picture is essentially not a picture for him, but the relationship between what is in the picture and what is in our heads. This is not connected to something resembling a prototype, indeed the opposite is true. It is about ignoring,

repudiating and forgetting what could be called prototypes. Fengel is fascinated by what is radically novel and thus wonderful. However this is not novel in the sense of something new, but in the sense of something different, something eternal, analysing what we see.

Being novel thus presents an epistemological paradox, because something can only be novel if it has a relationship to what is already well-known. Otherwise we would not perceive it as novel, indeed we would probably not perceive it at all. These inquisitive pictures are therefore about the structures of reality, the fiction of reality, models for approaching this reality, and agreeing about the nature of reality and the world that we live in. That is more or less what Wittgenstein called a fact.

Yet Fengel does not take the mystery away from the objects. The more precisely he looks at them – the wood, the ape, the giant eye – all the stranger and more unsettling they seem. The closer he comes to the objects the more they retreat – it is a science of observation which depends on the contradictory experience that precision produces blurring, that refinement creates coarsening, and that orange is sometimes merely orange just as blue is nothing more than blue.

It could be said that his photos are works spread over the pictorial dissection table. The lens is his surgical instrument and our world is the object. Martin Fengel is conducting a kind

of present-day archaeology, but without the belief that a past that can be interpreted ever

existed. His pictures are thus always facing nothingness. As Wittgenstein puts it, “Form is the possibility of structure.”

Sense is a word that Wittgenstein applies very carefully, indeed almost scrupulously. Sense is something that Fengel’s photos almost entirely lack. Sense is something that science does not seek to find. Sense is something for a poetry album, for evenings accompanied by red wine. It is a stranger to reality. And only this reality counts for the positivist Fengel. “What a picture represents is its sense”, comments Wittgenstein.

And what the picture represents can by all means also be sensual. Yet everything that could be beautiful or could be seen as poetic in these pictures is a result of external attribution. The pictures themselves avoid this simple definition. These pictures, despite their clarity, are evasive. They remain material.

That is also because of their objects, or what we see and what we think we see. A mirror and a curtain, a zig-zag pattern on the floor, the picture of a hammer in a golden frame – Martin Fengel is a field researcher in his work, collecting, recording, archiving, roaming the world from Bangkok to Mexico or from Arkansas to the Munich district of Pasing. Some of what he finds is remote and some of it is everyday; Martin Fengel’s world does not distinguish between the two, and indeed – and this was the truth revealed by Pop Art – neither does the world itself.

This lack of differentiation in observing, this benevolence, is exactly how Fengel’s relationship with Pop can best be described. That, and the fact that he took up photography in the late 1980s and early 1990s, when it still seemed that the whole world had transformed itself into its own surface. Fengel certainly learned the positivism of Pop, fascinated as he is by the shell of our being, by the shapes of our life, by the game pieces of sense, and by the beautiful folds of nothingness. Yet he has kept his distance from a simple affirmation of what he sees and what we see.

He also learned something that he could take with him into the post-Pop era, our age, when pictures have turned and are again competing with one another. Nothing is harmless and nothing is as it seems. A direct gaze is all the more important, and it is all the more understandable that this gaze engenders a stance that might be called melancholy if it were not that our own sadness is reflected in these photos – photos that are in themselves only photos, and yet become so much more when the observer confronts them.

Now the art – the truth that Wittgenstein was referring to – is to stage this relationship between the image (which is reticent about its history and meaning) and the observer (who is looking for nothing more than that: meaningful connotations, biographical references, something familiar). It is astounding that the photos withstand this approach without actually rejecting it. It is precisely their distance that allows them to dispense some comfort in a melancholic world that knows no desperation. It sometimes seems that melancholy even serves as protection against too much contact with the hard corners and sharp edges of the world.

Melancholy and comfort are thus the cornerstones of this architecture of nothingness that Martin Fengel pursues in his photography. Melancholy and comfort are the result of this photographic activity rather than an intrinsic part of the aesthetic agenda. Melancholy and comfort are the new dawns in these pictures; they are what art can achieve, akin to what Rainald Goetz demands of art in Jeff Koons, his drama about artists and the 1990s: “That every picture, even abstractly, has to deal naively in the sensory information of world facts. And that there are therefore no solutions - for anything, that in its own way every picture is a completely new opening of the eyes, first thing in the morning, not knowing anything, that only later becomes complex and awkward, broken, difficult, ruined, etc. etc.”

So, world facts, right. And quite naive. Or just benevolent.

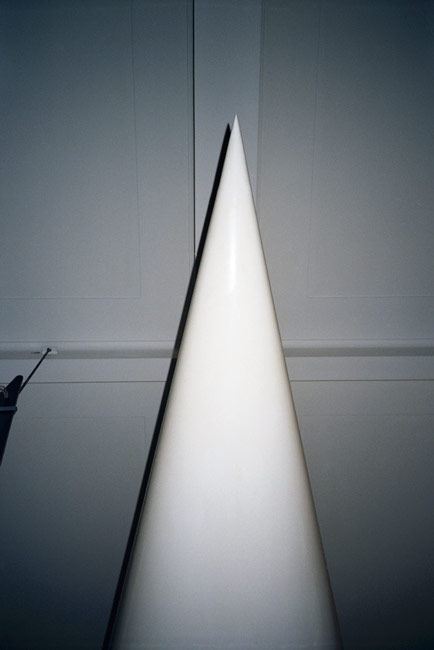

installation view, Fotomuseum, Munich, 2008

installation view, Fotomuseum, Munich, 2008 installation view, Fotomuseum, Munich, 2008

installation view, Fotomuseum, Munich, 2008