Mobil 100 | 1999 | INFO

Mobil 100 | 1999 | INFOMobil 100

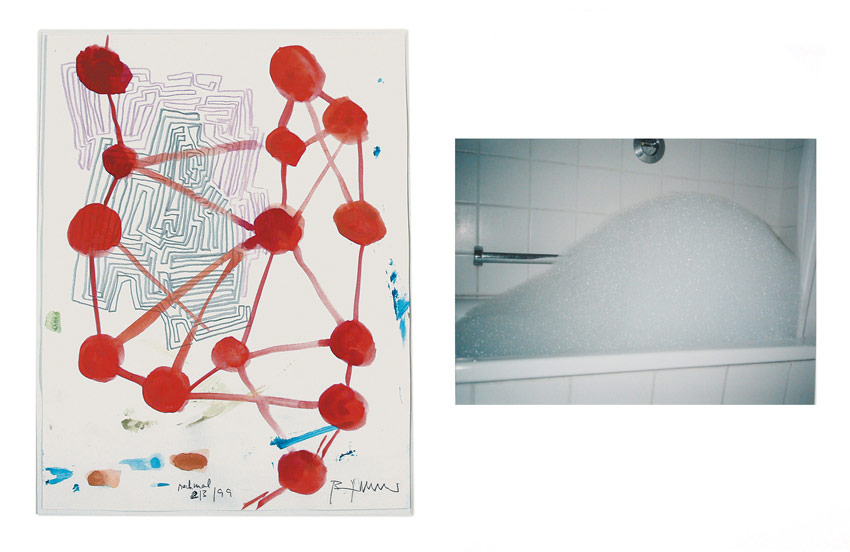

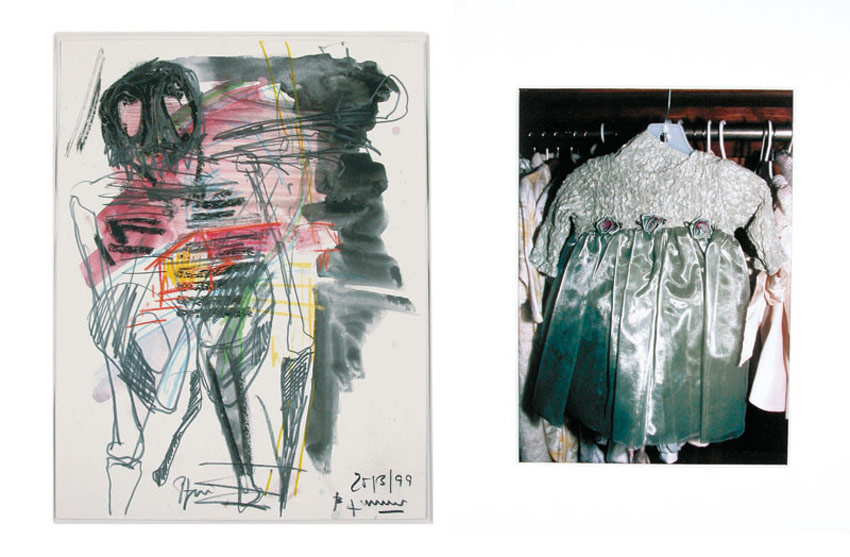

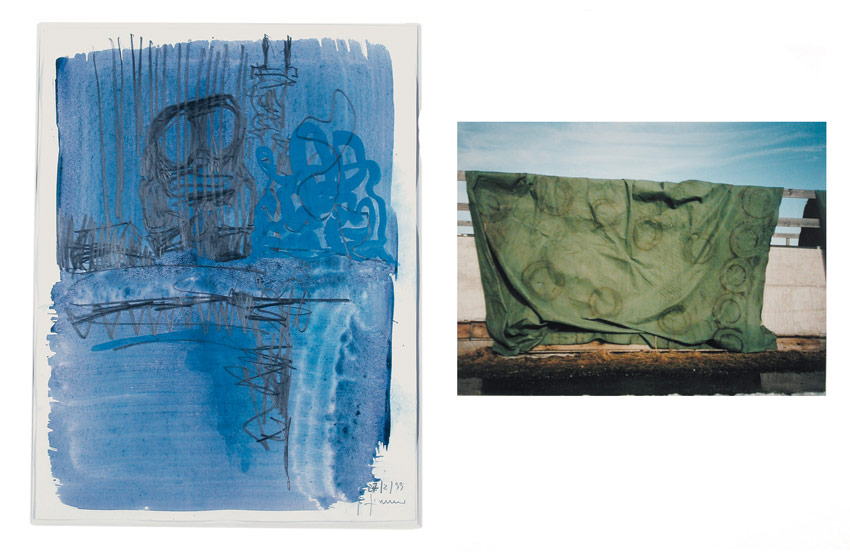

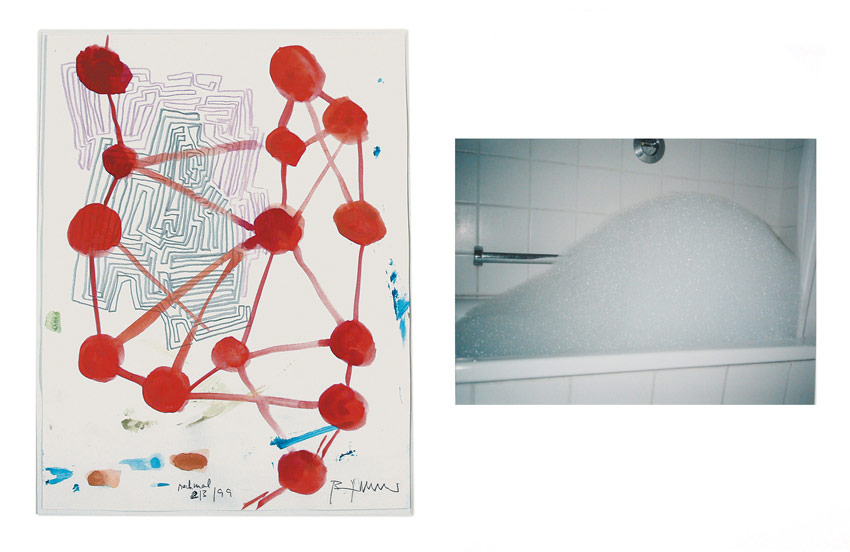

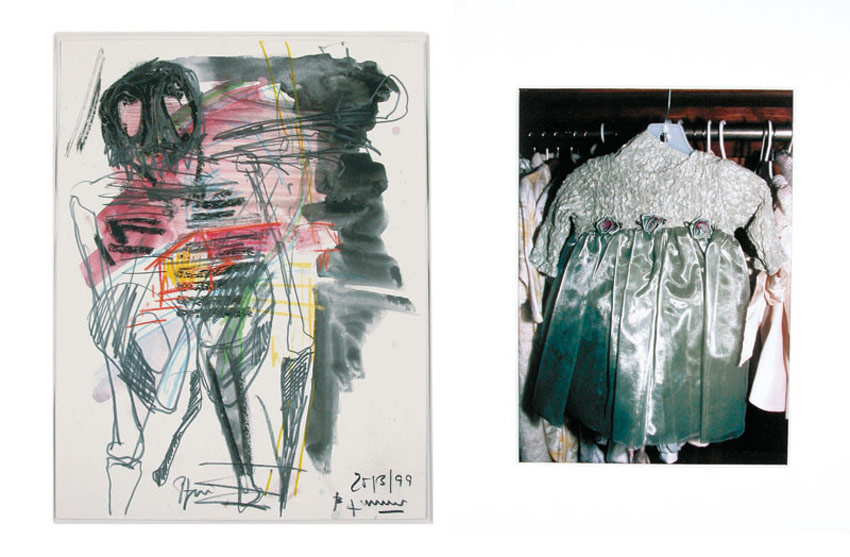

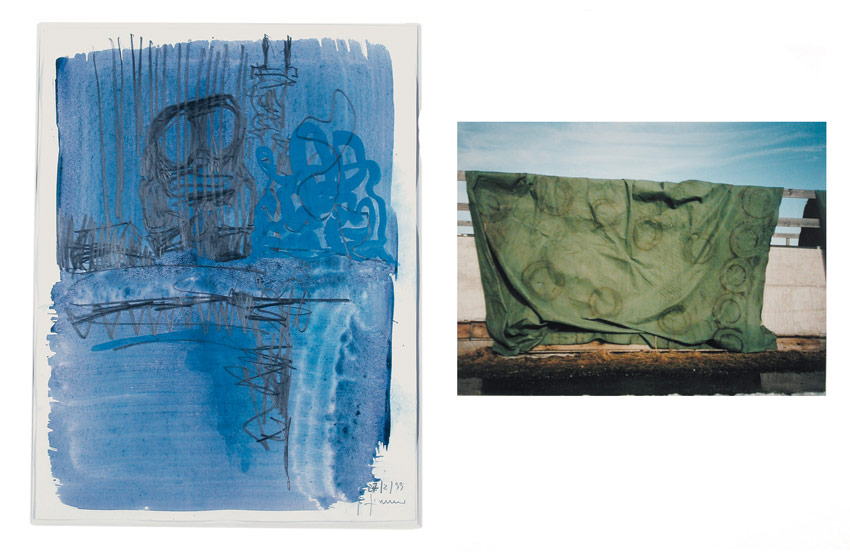

an exchange between Bernd Zimmer and Martin FengelBernd Zimmer and Martin Fengel jointly developed a series of works called Mobil 100 in the hundred days commencing 1 January 1999. One photographic work and one piece of writing were produced every day in various global locations, using a range of techniques. In so doing, each artist conceptually devoted each of the hundred days of the joint project to an indirect communicative process that is reflected in the works. Although the artists occasionally contacted each other during this period, they deliberately avoided exchanging details of the joint project. Works that were created simultaneously were subsequently framed side by side, and collected in an artist’s book; the design of the catalogue is also based on the form of the artist’s book. The technique produced some interesting overlaps – the works frequently displayed similarities, whereas on other days there were discrepancies and differences. The title of the series refers to the idea of a global approach that transcends boundaries, both directly and indirectly transforming the images seen in reality into photographic and written works produced on the move. Bernd Zimmer signed and dated all the works, so that they can be classified with certainty according to specific places and times.

These works, created parallel to one other on one hundred successive days, pick up on – without making a deliberate reference to – the tradition of artistic projects focusing on communication, rooted in classical modernism and the twentieth century. They range from the associative dessins communiqué of the surrealist circle surrounding André Breton to letters as an art form; from mail art networks to special forms, such as collections created by post.[1] One happening by Bernd Zimmer and Daniel Nagel dated 1980 displayed a direct link to this tradition. The two artists sent individually-designed postcards to each other from various places in the world every day for three months. Rather than focusing on the principle of sending and receiving, Mobil 100 goes one step further in exploring the experimental aspect of the connection between space and time and the coincidental confrontation between two opposing media. The project thus also aims to conduct an experimental search for areas of visual creative tension.

Travel is a source of inspiration for both artists. In this particular piece they have taken a global approach, creating a continental visual connection through indirect artistic communication.

The motifs reflect the different places they visited on different continents along the way. Bernd Zimmer’s first works, for instance, display African motifs, influenced by his stay in Namibia. By contrast, Martin Fengel took photographs in Los Angeles and Munich.

The subject matter and colouration of Bernd Zimmer’s works on paper are a reaction to stimuli which are subjectively transformed from memory. When seen independently of the background context, they almost represent a kind of imaginary and autonomous travel sketchbook translating impressions and recollections from deeply-held memories into line and colour.[2] In a departure from normal practice and in recognition of the set time constraints, the works were created as soon as possible in each location, rather than waiting until the artist returned to the studio.[3] The works were executed in a vast range of techniques. Mixed-media works include drawings in pencil, charcoal, chalk, or biro, combined with watercolours and gouaches. Only a very few drawings make use of a single, sparse technique alone. Figurative sketches are more frequent in Zimmer’s works on paper than in his paintings, and they alternate with abstract landscapes, drawings of nature, or abstract sketches of motifs. The concentration on a single section or detail is characteristic for Zimmer. Isolated and dominant in the picture, this kind of detail creates an evocative visual power when combined with line and colour. When Bernd Zimmer is engaged in graphic art he remains a painter; equally, graphic elements are occasionally evident in his paintings. In this respect, a connection to painting is recognisable in the works.[4] Motifs such as isolated details of X-rays of bones or teeth appear repeatedly as signs of individual and collective inborn feelings towards nature. The works are restricted to two tones, such as blue and yellow or blue and red, which reflect the colours usually chosen for painted landscapes. The associative nature of these works on paper is the result of drawing from and processing an internal pool of genuinely-experienced images. Reality is selectively and subjectively transformed. The early pictures, created in the first few days of the project, present drawn and painted figures resembling archaic codes reminiscent of prehistoric human pictures and symbols. They are evidence of the search for original existential forms that form the basis of Bernd Zimmer’s work.[5] With the openness and endless wealth of his graphic and painterly execution, this search repeatedly exhibits new visual ways to produce a visual potential force; it is the search for deliberate cracks and discrepancies. This basic idea lies behind the association with the opposing medium of photography. The sometimes radical connection of the works on paper to Martin Fengel’s photographs explores the options presented by the confrontations of two antithetical media. Yet anybody who expects these two different “products of day-to-day work” to be irreconcilable is forced to concede that they in fact result in both conflict and harmony. While the semantic fields are far apart in terms of both form and content for some works, in others they merge and in doing so generate associations. For both artists visual stimuli lead to authentic results when searching for the highest possible determination of reality.

There is no corrective or editing mode in the medium of photography as such, and Bernd Zimmer also adopts the same principle when he creates works on paper in a spontaneous and permanent process.

Martin Fengel’s photography focuses on the exceptional aspect of the commonplace. He documents the photos he has taken throughout the day, finally choosing one that he finds best represents that period of time in terms of mood and events. His pictures show sections and details, concentrating on everyday motifs that are both commonplace and yet exceptional; despite their everyday nature they seem strange, or are rendered unfamiliar by the photographer’s angle and the style of the shot. The photos that Martin Fengel take deliberately vary in quality, selection of motif, and intensity. The pictures trace a seismographic curve within which the hundred units of time can be characterised as an atmospheric whole. The time factor – independent of space, in other words the surroundings in which the photograph is taken – is presented in a different manner to Bernd Zimmer’s works on paper. Various time-related situations and the realisation of a subjective sense of time become apparent in the photographs. We are thus confronted in some cases by pictures that seem to be the spontaneous snapshots of an amateur photographer, capturing something as banal as a TV, a man telephoning, or the steering wheel of a car. In other photos the motifs appear to be consciously selected and framed with some deliberation. The different moods and events captured over so many days correspond to the range of pictorial language and the way motifs are handled.

The locations behind the photographs are not identifiable, because only sections of reality are ever shown; at best we can guess where the artist took the photo based on a few details. The sections of reality are brought into close-up by the camera, and this impression of the motifs being multiplied in size also makes them more diverse and wide-ranging. Generally speaking, however, there are certain key themes, such as the dialectic of countryside and city: the tense interrelationship between the natural world and the artificial environment created by people, as seen from the subjective view of the photographer.

The Mobil 100 project by Martin Fengel and Bernd Zimmer uses the factors of space and time to interlink controversial pictures with interpretations, and relationships of form and content. Imaginary potential is transformed within the tangible reality of Martin Fengel’s photographs, while reality is rendered visible in the imaginary world of Bernd Zimmer’s works on paper. External and internal pictures are composed as if they were subjective and imaginary jigsaw pieces of different world views. They diverge and correspond, evoking a visual magic that reveals a creative force behind the project as a whole.

Anja Eichler[1] Brèton described the group game cadavre exquis (exquisite corpse) in his text Le cadaver exquis thus: Game of folded paper played by several people, who compose a sentence or drawing without anyone seeing the preceding collaboration or collaborations.

[2] According to Bernd Zimmer they are always imaginary forms that have actually been seen. Zimmer, ed. Hannelore Paflik-Huber (Cologne 2002), p.93.

[3] P. A. Riedl, “Unterwegs”,, in Zimmer, ed., Hannelore Paflik-Huber, (Cologne 2002), p. 96 (translated) describes the chronological relationship between Zimmer’s journey and the mental and practical approach he took to dealing with his impressions, “The series of desert pictures from the Libya trip in spring 1993 only appeared in autumn that year, and there were also a number of months between the Polynesian journey in early 1995 and the first pictures of the South Seas. The second, mental part of the journey takes us back to a past that is by necessity both reservoir and filter.”

[4] See also Hannelore Paflik-Huber and Hans Dieter Huber on the analogies between works on paper and paintings: “Zeichnen als Konstruktion von Welt. Die Papierarbeiten von Bernd Zimmer”, in Georg Reinhardt, ed.,, Bernd Zimmer. Aus der Ferne. NÄHE. Arbeiten auf Papier 1977-1997 (Cologne 1998), pp.138–9.

[5] There are various descriptions of this approach, such as Beat Wyss, “Ich sehe”, in Zimmer, ed., Hannelore Paflik-Huber (Cologne 2002), p. 91.

Mobil 100 | 1999 | INFO

Mobil 100 | 1999 | INFOMobil 100

an exchange between Bernd Zimmer and Martin FengelBernd Zimmer and Martin Fengel jointly developed a series of works called Mobil 100 in the hundred days commencing 1 January 1999. One photographic work and one piece of writing were produced every day in various global locations, using a range of techniques. In so doing, each artist conceptually devoted each of the hundred days of the joint project to an indirect communicative process that is reflected in the works. Although the artists occasionally contacted each other during this period, they deliberately avoided exchanging details of the joint project. Works that were created simultaneously were subsequently framed side by side, and collected in an artist’s book; the design of the catalogue is also based on the form of the artist’s book. The technique produced some interesting overlaps – the works frequently displayed similarities, whereas on other days there were discrepancies and differences. The title of the series refers to the idea of a global approach that transcends boundaries, both directly and indirectly transforming the images seen in reality into photographic and written works produced on the move. Bernd Zimmer signed and dated all the works, so that they can be classified with certainty according to specific places and times.

These works, created parallel to one other on one hundred successive days, pick up on – without making a deliberate reference to – the tradition of artistic projects focusing on communication, rooted in classical modernism and the twentieth century. They range from the associative dessins communiqué of the surrealist circle surrounding André Breton to letters as an art form; from mail art networks to special forms, such as collections created by post.[1] One happening by Bernd Zimmer and Daniel Nagel dated 1980 displayed a direct link to this tradition. The two artists sent individually-designed postcards to each other from various places in the world every day for three months. Rather than focusing on the principle of sending and receiving, Mobil 100 goes one step further in exploring the experimental aspect of the connection between space and time and the coincidental confrontation between two opposing media. The project thus also aims to conduct an experimental search for areas of visual creative tension.

Travel is a source of inspiration for both artists. In this particular piece they have taken a global approach, creating a continental visual connection through indirect artistic communication.

The motifs reflect the different places they visited on different continents along the way. Bernd Zimmer’s first works, for instance, display African motifs, influenced by his stay in Namibia. By contrast, Martin Fengel took photographs in Los Angeles and Munich.

The subject matter and colouration of Bernd Zimmer’s works on paper are a reaction to stimuli which are subjectively transformed from memory. When seen independently of the background context, they almost represent a kind of imaginary and autonomous travel sketchbook translating impressions and recollections from deeply-held memories into line and colour.[2] In a departure from normal practice and in recognition of the set time constraints, the works were created as soon as possible in each location, rather than waiting until the artist returned to the studio.[3] The works were executed in a vast range of techniques. Mixed-media works include drawings in pencil, charcoal, chalk, or biro, combined with watercolours and gouaches. Only a very few drawings make use of a single, sparse technique alone. Figurative sketches are more frequent in Zimmer’s works on paper than in his paintings, and they alternate with abstract landscapes, drawings of nature, or abstract sketches of motifs. The concentration on a single section or detail is characteristic for Zimmer. Isolated and dominant in the picture, this kind of detail creates an evocative visual power when combined with line and colour. When Bernd Zimmer is engaged in graphic art he remains a painter; equally, graphic elements are occasionally evident in his paintings. In this respect, a connection to painting is recognisable in the works.[4] Motifs such as isolated details of X-rays of bones or teeth appear repeatedly as signs of individual and collective inborn feelings towards nature. The works are restricted to two tones, such as blue and yellow or blue and red, which reflect the colours usually chosen for painted landscapes. The associative nature of these works on paper is the result of drawing from and processing an internal pool of genuinely-experienced images. Reality is selectively and subjectively transformed. The early pictures, created in the first few days of the project, present drawn and painted figures resembling archaic codes reminiscent of prehistoric human pictures and symbols. They are evidence of the search for original existential forms that form the basis of Bernd Zimmer’s work.[5] With the openness and endless wealth of his graphic and painterly execution, this search repeatedly exhibits new visual ways to produce a visual potential force; it is the search for deliberate cracks and discrepancies. This basic idea lies behind the association with the opposing medium of photography. The sometimes radical connection of the works on paper to Martin Fengel’s photographs explores the options presented by the confrontations of two antithetical media. Yet anybody who expects these two different “products of day-to-day work” to be irreconcilable is forced to concede that they in fact result in both conflict and harmony. While the semantic fields are far apart in terms of both form and content for some works, in others they merge and in doing so generate associations. For both artists visual stimuli lead to authentic results when searching for the highest possible determination of reality.

There is no corrective or editing mode in the medium of photography as such, and Bernd Zimmer also adopts the same principle when he creates works on paper in a spontaneous and permanent process.

Martin Fengel’s photography focuses on the exceptional aspect of the commonplace. He documents the photos he has taken throughout the day, finally choosing one that he finds best represents that period of time in terms of mood and events. His pictures show sections and details, concentrating on everyday motifs that are both commonplace and yet exceptional; despite their everyday nature they seem strange, or are rendered unfamiliar by the photographer’s angle and the style of the shot. The photos that Martin Fengel take deliberately vary in quality, selection of motif, and intensity. The pictures trace a seismographic curve within which the hundred units of time can be characterised as an atmospheric whole. The time factor – independent of space, in other words the surroundings in which the photograph is taken – is presented in a different manner to Bernd Zimmer’s works on paper. Various time-related situations and the realisation of a subjective sense of time become apparent in the photographs. We are thus confronted in some cases by pictures that seem to be the spontaneous snapshots of an amateur photographer, capturing something as banal as a TV, a man telephoning, or the steering wheel of a car. In other photos the motifs appear to be consciously selected and framed with some deliberation. The different moods and events captured over so many days correspond to the range of pictorial language and the way motifs are handled.

The locations behind the photographs are not identifiable, because only sections of reality are ever shown; at best we can guess where the artist took the photo based on a few details. The sections of reality are brought into close-up by the camera, and this impression of the motifs being multiplied in size also makes them more diverse and wide-ranging. Generally speaking, however, there are certain key themes, such as the dialectic of countryside and city: the tense interrelationship between the natural world and the artificial environment created by people, as seen from the subjective view of the photographer.

The Mobil 100 project by Martin Fengel and Bernd Zimmer uses the factors of space and time to interlink controversial pictures with interpretations, and relationships of form and content. Imaginary potential is transformed within the tangible reality of Martin Fengel’s photographs, while reality is rendered visible in the imaginary world of Bernd Zimmer’s works on paper. External and internal pictures are composed as if they were subjective and imaginary jigsaw pieces of different world views. They diverge and correspond, evoking a visual magic that reveals a creative force behind the project as a whole.

Anja Eichler[1] Brèton described the group game cadavre exquis (exquisite corpse) in his text Le cadaver exquis thus: Game of folded paper played by several people, who compose a sentence or drawing without anyone seeing the preceding collaboration or collaborations.

[2] According to Bernd Zimmer they are always imaginary forms that have actually been seen. Zimmer, ed. Hannelore Paflik-Huber (Cologne 2002), p.93.

[3] P. A. Riedl, “Unterwegs”,, in Zimmer, ed., Hannelore Paflik-Huber, (Cologne 2002), p. 96 (translated) describes the chronological relationship between Zimmer’s journey and the mental and practical approach he took to dealing with his impressions, “The series of desert pictures from the Libya trip in spring 1993 only appeared in autumn that year, and there were also a number of months between the Polynesian journey in early 1995 and the first pictures of the South Seas. The second, mental part of the journey takes us back to a past that is by necessity both reservoir and filter.”

[4] See also Hannelore Paflik-Huber and Hans Dieter Huber on the analogies between works on paper and paintings: “Zeichnen als Konstruktion von Welt. Die Papierarbeiten von Bernd Zimmer”, in Georg Reinhardt, ed.,, Bernd Zimmer. Aus der Ferne. NÄHE. Arbeiten auf Papier 1977-1997 (Cologne 1998), pp.138–9.

[5] There are various descriptions of this approach, such as Beat Wyss, “Ich sehe”, in Zimmer, ed., Hannelore Paflik-Huber (Cologne 2002), p. 91.

Installation view, studio Bernd Zimmer, 1999

Installation view, studio Bernd Zimmer, 1999 Installation view, studio Bernd Zimmer, 1999

Installation view, studio Bernd Zimmer, 1999